The Breadboard & Multimeter Masterclass (Build Your First Circuit)

Stop guessing and start building. Learn how to decode the breadboard, master the multimeter, and build your very first working LED circuit without burning anything down.

Welcome to Day 4.

Look at the device you are reading this on. Phone? Laptop? Desktop? Inside that device are billons—yes, billions—of microscopic switches turning on and off billions of times per second. Those switches are not mechanical. They have no moving parts. They never wear out. They are Transistors.

In 1947, a transistor was the size of your hand. Today, we fit 50 billion of them on a chip the size of your fingernail. It is, without hyperbole, the most important invention in human history.

Today, you are going to hold one in your hand. And you are going to make it do your bidding.

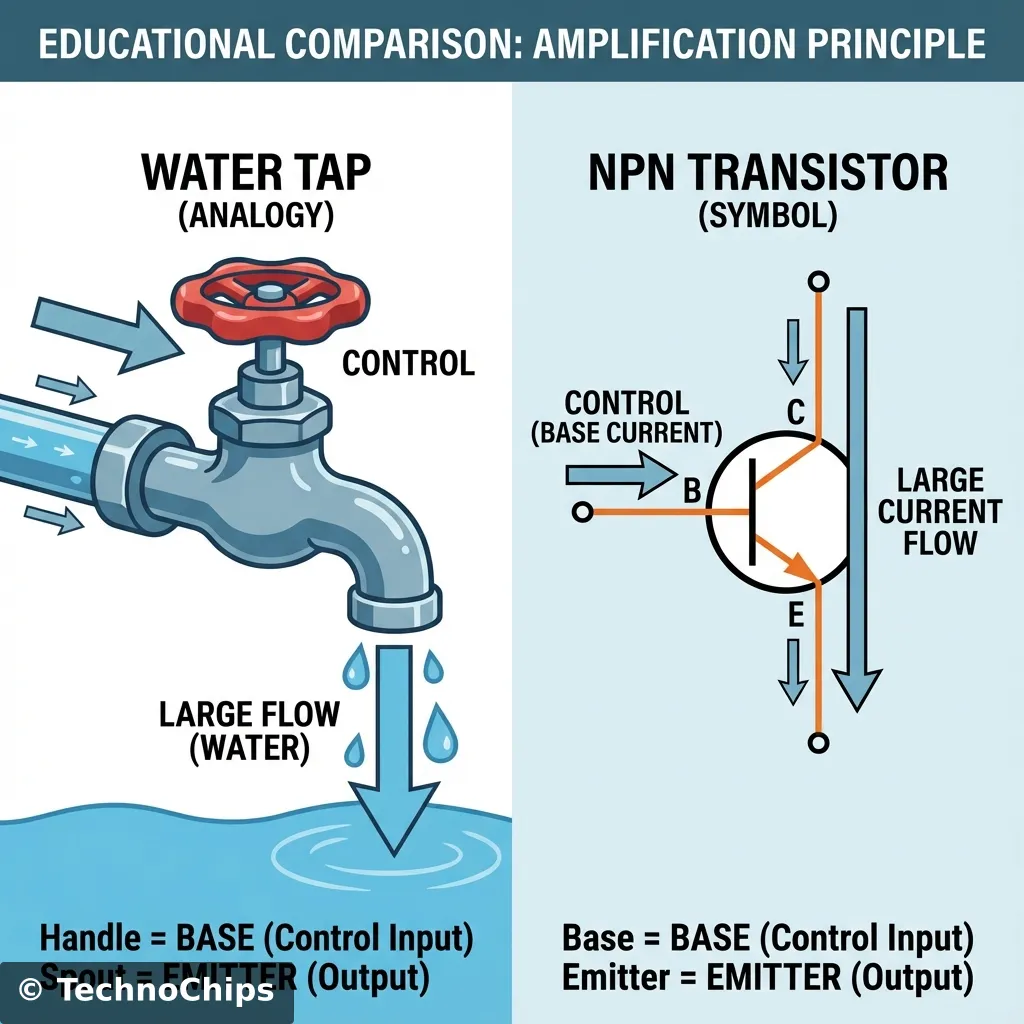

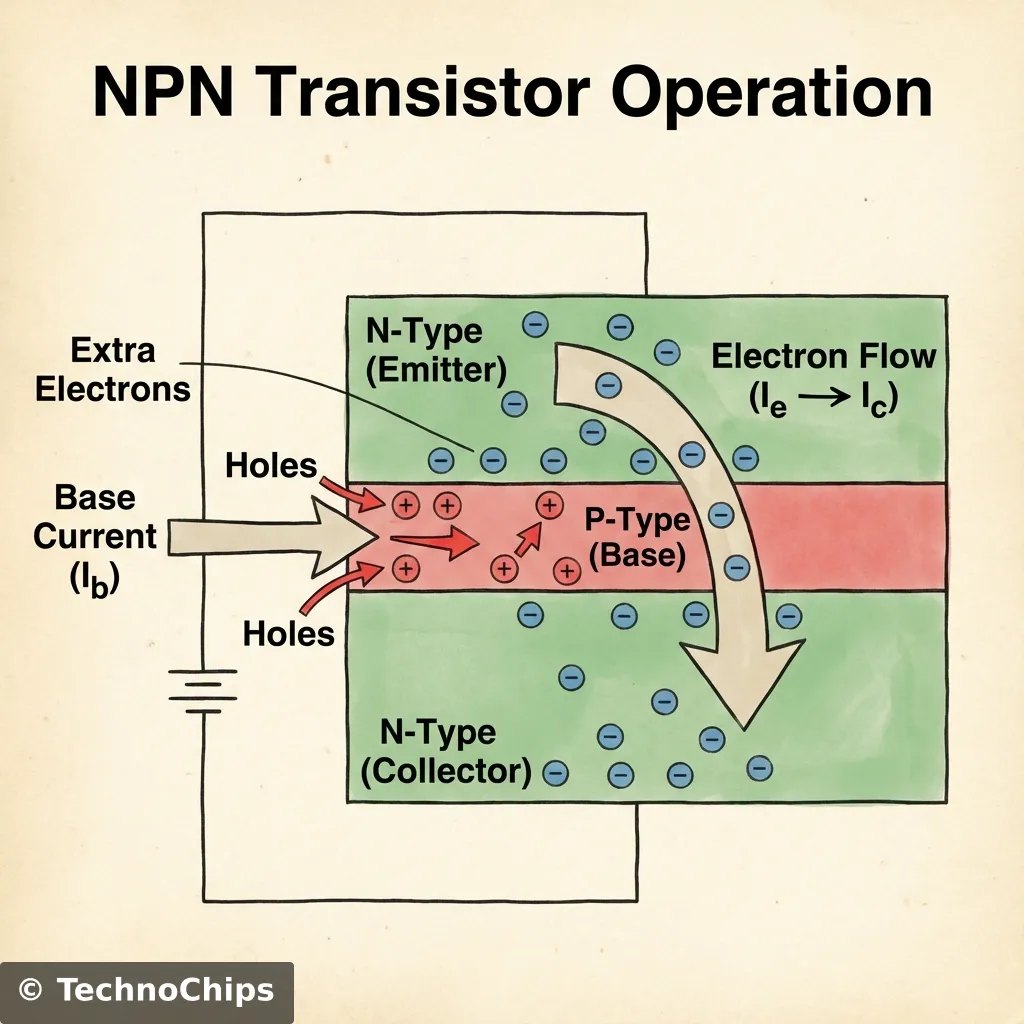

Remove the physics degree. Forget “Quantum Tunneling” and “Depletion Regions” for a second. A Transistor is a Digital Valve.

Think of a water tap.

A transistor is identical.

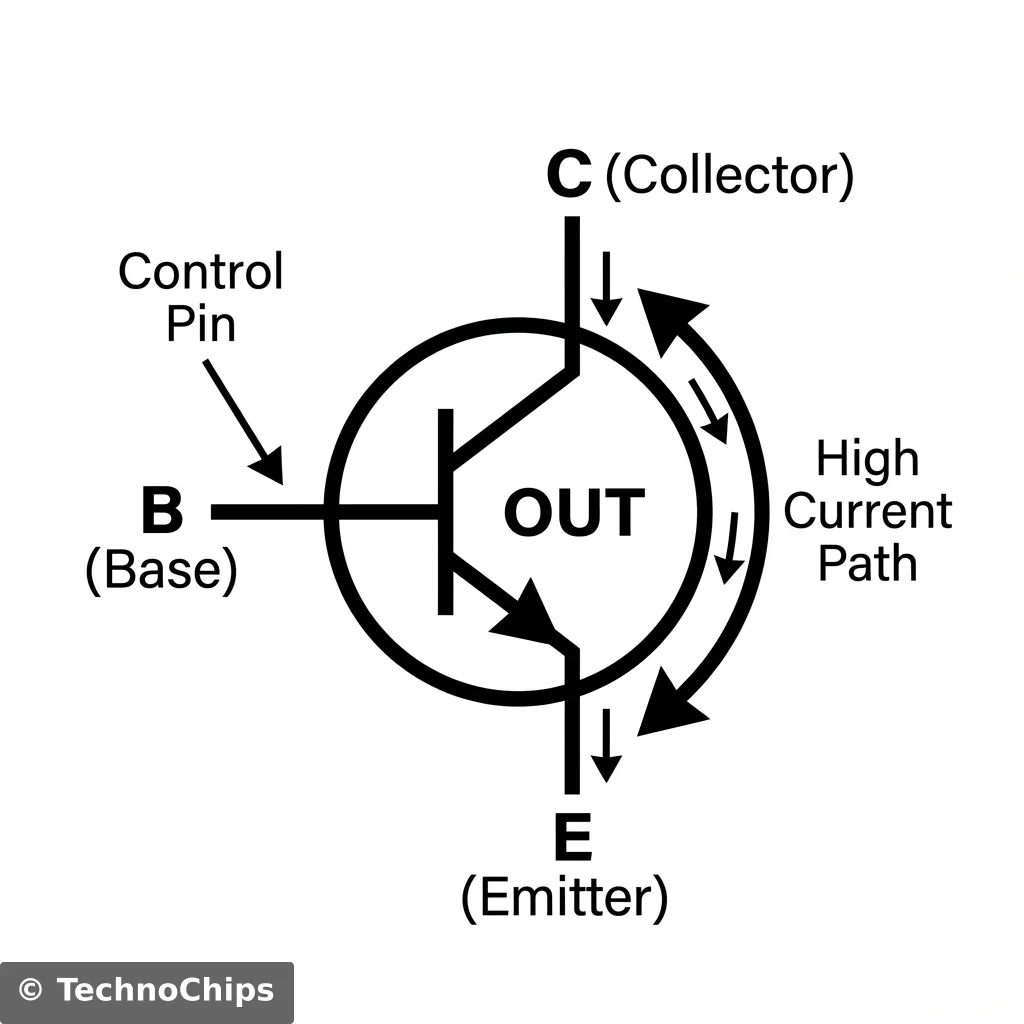

If you push a tiny current into the Base, it opens the gate, and a huge current flows from Collector to Emitter.

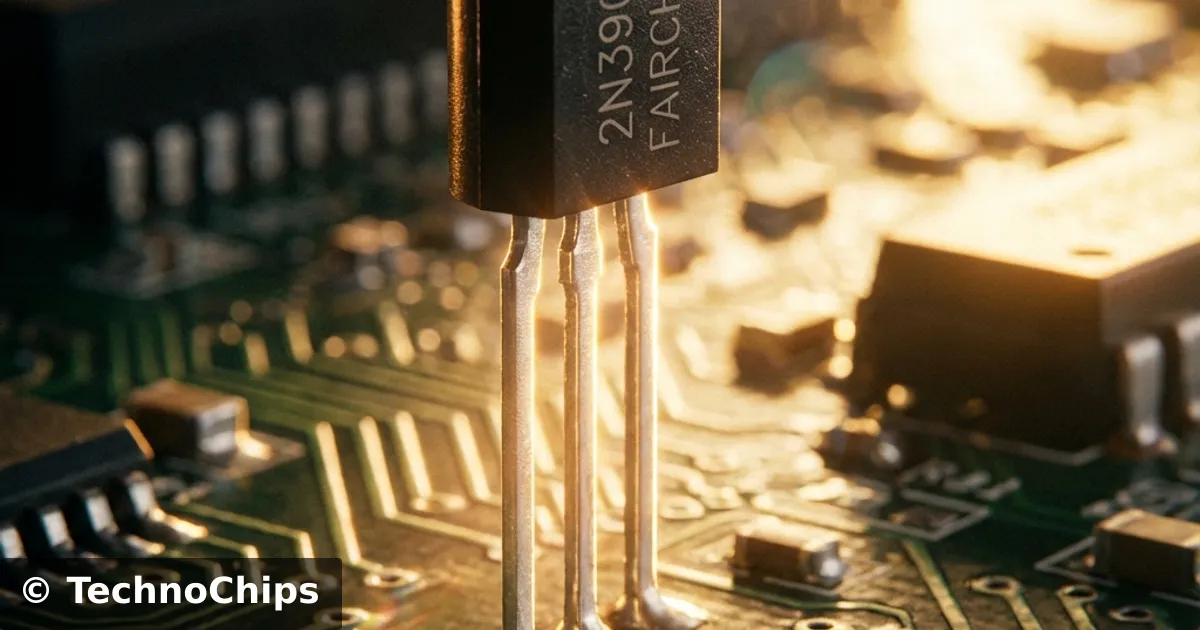

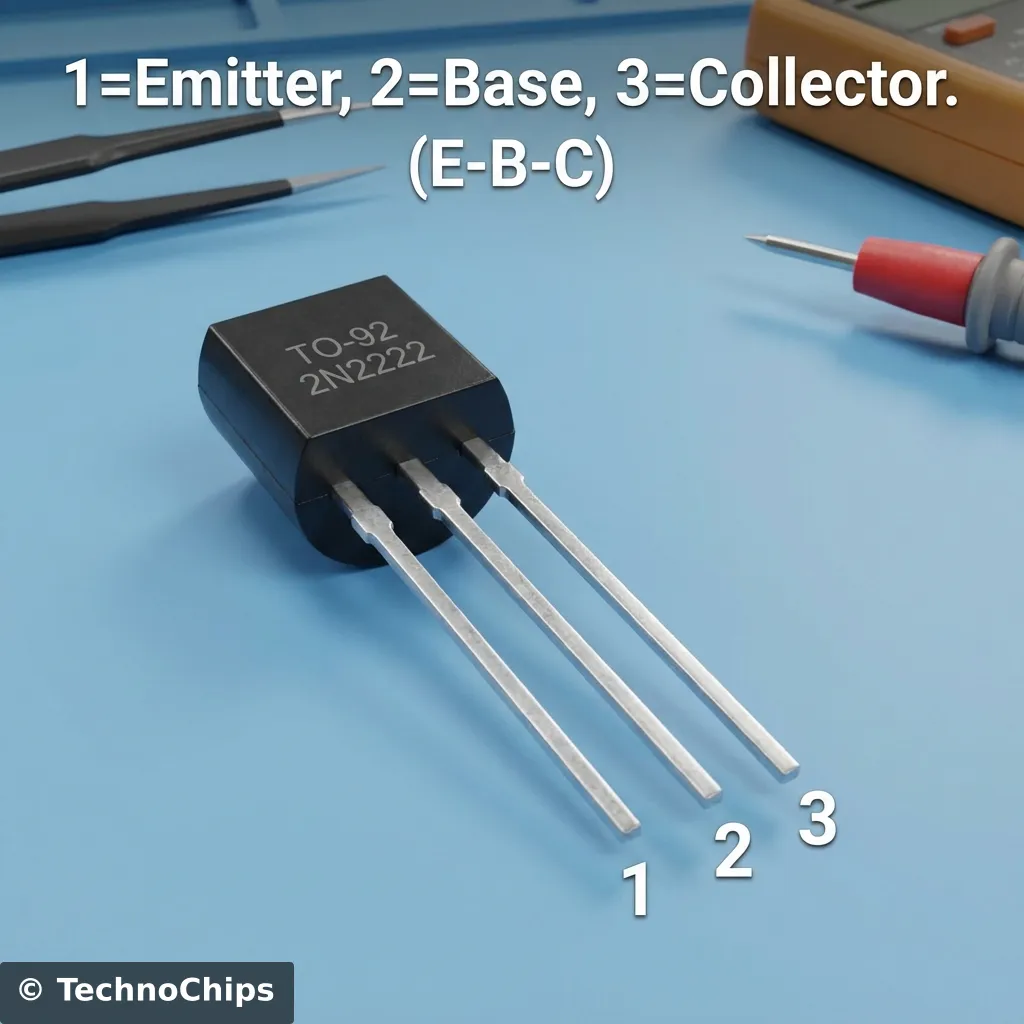

We are using the 2N2222 (or BC547). This is an NPN transistor. It looks like a tiny black D-shape with three legs.

Holding the flat side facing you, legs pointing down:

(Note: If you are using a BC547, the pins might be reversed C-B-E. Always check the datasheet! But for 2N2222, it’s usually E-B-C).

On a schematic, it looks like this. The arrow points OUT.

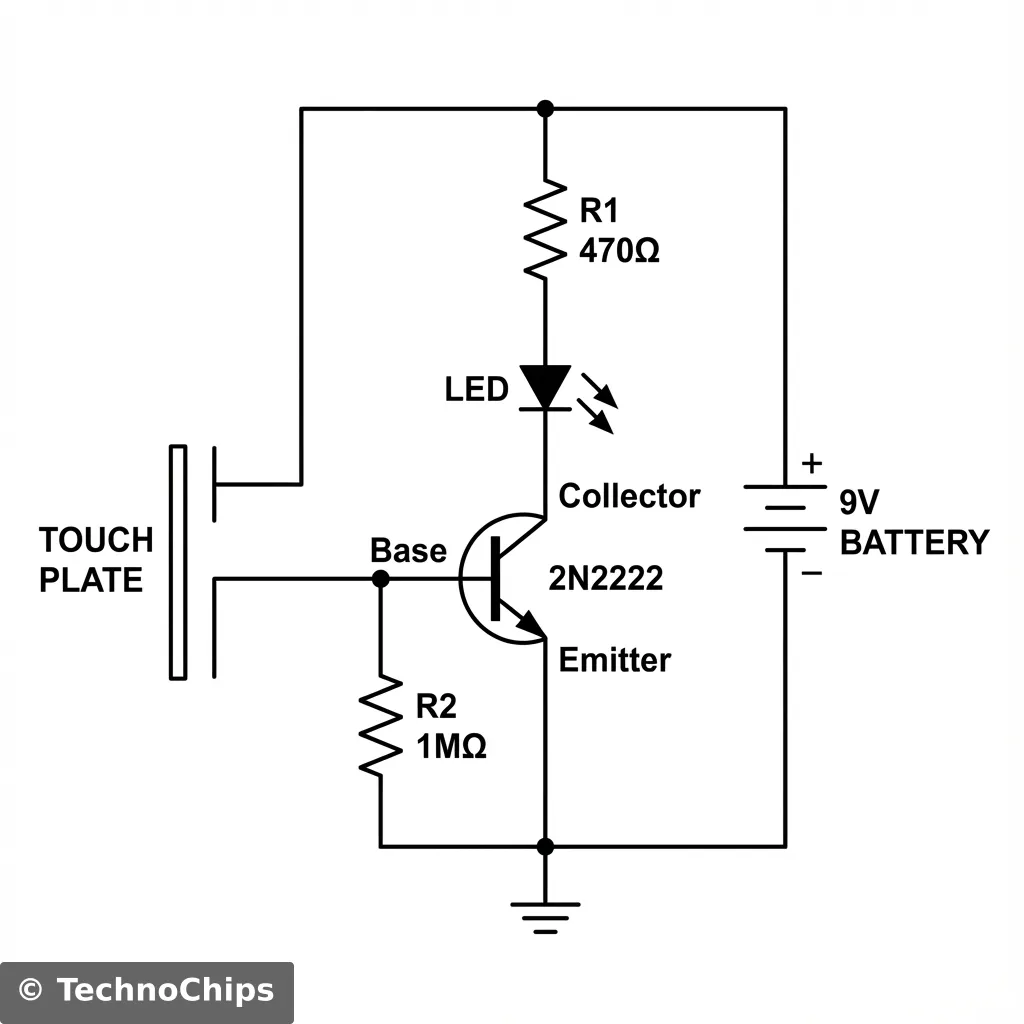

We are going to build a circuit where the “Switch” is literally your skin. Your body has resistance, but it conducts enough electricity to trigger a transistor.

The Goal: Touch a wire, LED turns on. Let go, LED turns off.

The Parts:

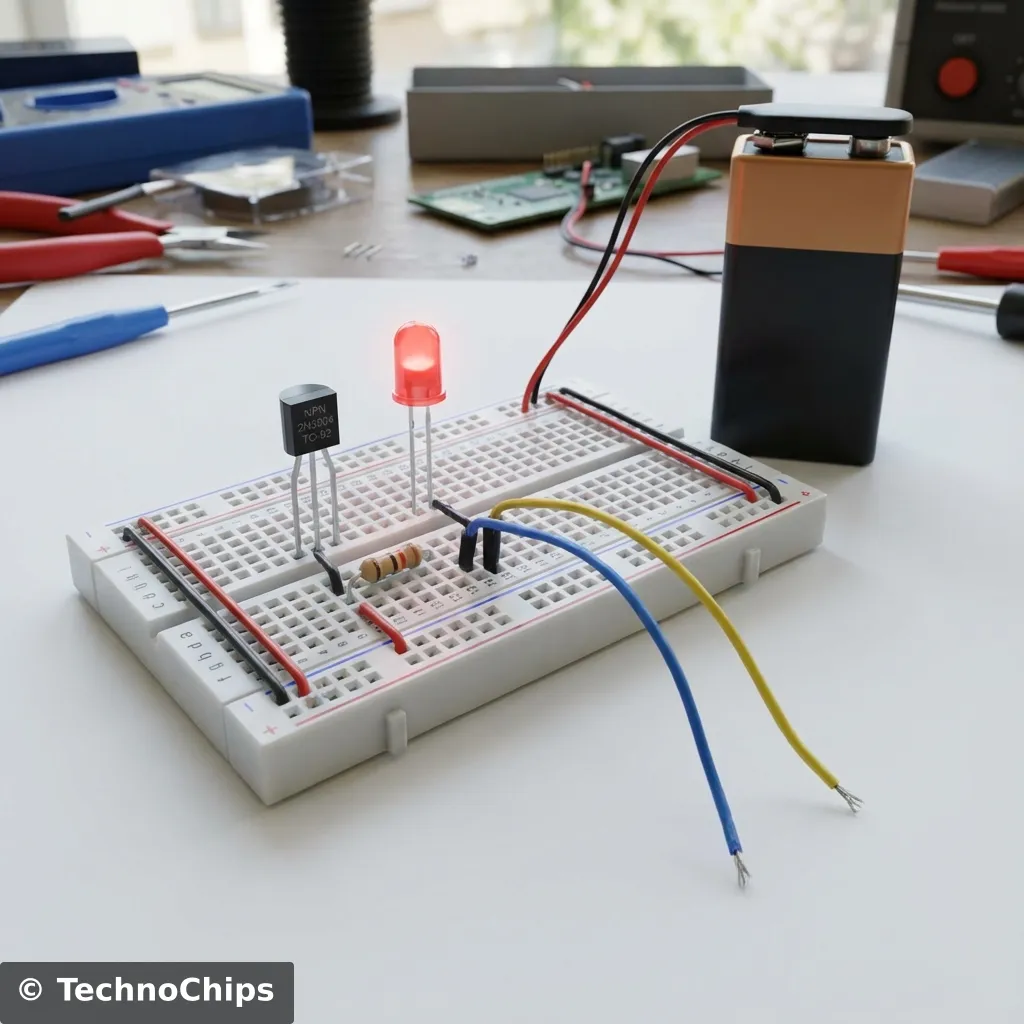

Put the transistor in three separate rows. Flat side facing you.

Connect a jumper from Row 10 (Emitter) directly to the Blue (-) Rail.

We put the LED before the transistor (on the Collector side).

Now, the control. Plug a long jumper wire into Row 11 (Base). Leave the other end dangling in the air. Plug another jumper wire into the Red (+) Rail. Leave the end dangling.

Plug in the battery. Nothing happens. The valve is closed. Now, grab the metal tip of the dangling “Base” wire with one finger. Grab the metal tip of the dangling “Positive” wire with the other finger.

The LED lights up.

9 Volts went through your body, through your fingers, into the Base of the transistor. The current was tiny (micro-amps). You couldn’t feel it. But the transistor felt it. It amplified that tiny signal ~100 times, opening the floodgates for the LED.

You just witnessed Gain. Every transistor has a rating called Beta (or hFE). For a 2N2222, Beta is usually ~100. This means: 1 electron into the Base allows 100 electrons to flow through the Collector. This is how your phone works. A tiny, weak Wi-Fi signal hits an antenna. It goes into a transistor. The transistor uses battery power to copy that signal and make it strong enough to drive a speaker.

We used the transistor as a Switch (On/Off). But it is also an Amplifier. If you send a fluctuating signal (like music) into the Base, the transistor mimics that fluctuation on the other side, but with more power. This is “Class A” amplification. The downside? It gets hot. The transistor is effectively a variable resistor, burning off excess energy as heat to regulate the flow. We will build a simple Speaker Amplifier in Week 2, but for now, just understand that switching and amplifying are two sides of the same coin.

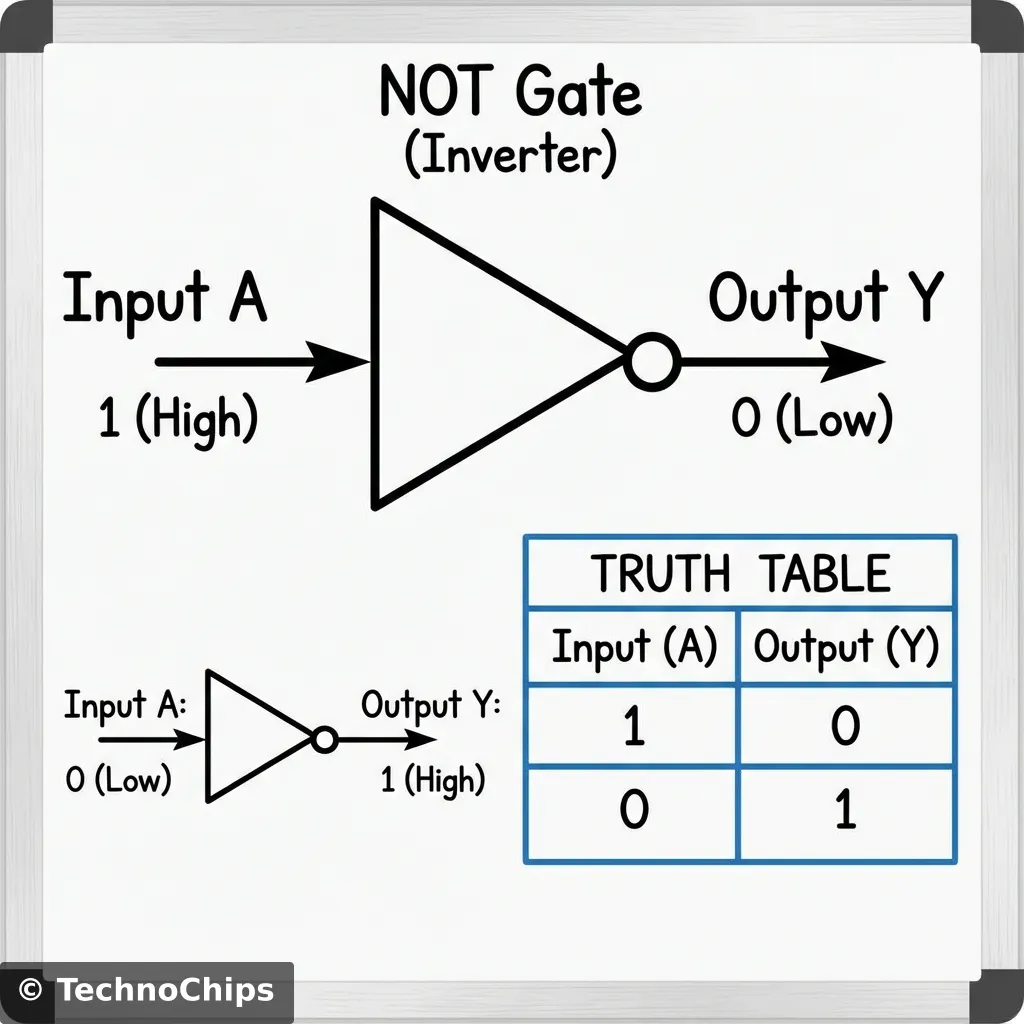

Computers think in 1s and 0s. How do we make a “0” from a “1”? We use a NOT Gate (Inverter).

Let’s modify our circuit.

When you turn the transistor ON (High Input): The path to ground becomes effortless (short circuit). The voltage at the Collector drops to 0V. The Output goes LOW.

When you turn the transistor OFF (Low Input): The path to ground is blocked. The voltage at the Collector floats up to 9V. The Output goes HIGH.

You just built the fundamental building block of CPU logic.

Every component has a manual called a Datasheet. Let’s decode the 2N2222. Search for “2N2222 datasheet” and you will see a table.

What if your fingers are too dry? Or you want to detect a static charge from a balloon? One transistor amplifies ~100x. What if we feed the output of Transistor A into the input of Transistor B? Gain = 100 x 100 = 10,000x.

Now, you don’t even need to touch the wire. Just bringing your hand near it might trigger it due to the electromagnetic field of your body. You just built a proximity sensor.

An NPN sandwich is a slice of P-type between two slices of N-type. Normally, electrons can’t jump across. But when we energize the middle P-layer (Base), it creates a bridge.

You might think, “I don’t use transistors.” You are wrong.

If all transistors vanished, civilization would collapse in 8 milliseconds.

We are using the TO-92 (The little plastic d-shape). But they come in all sizes.

It works on paper. But does it work on your desk?

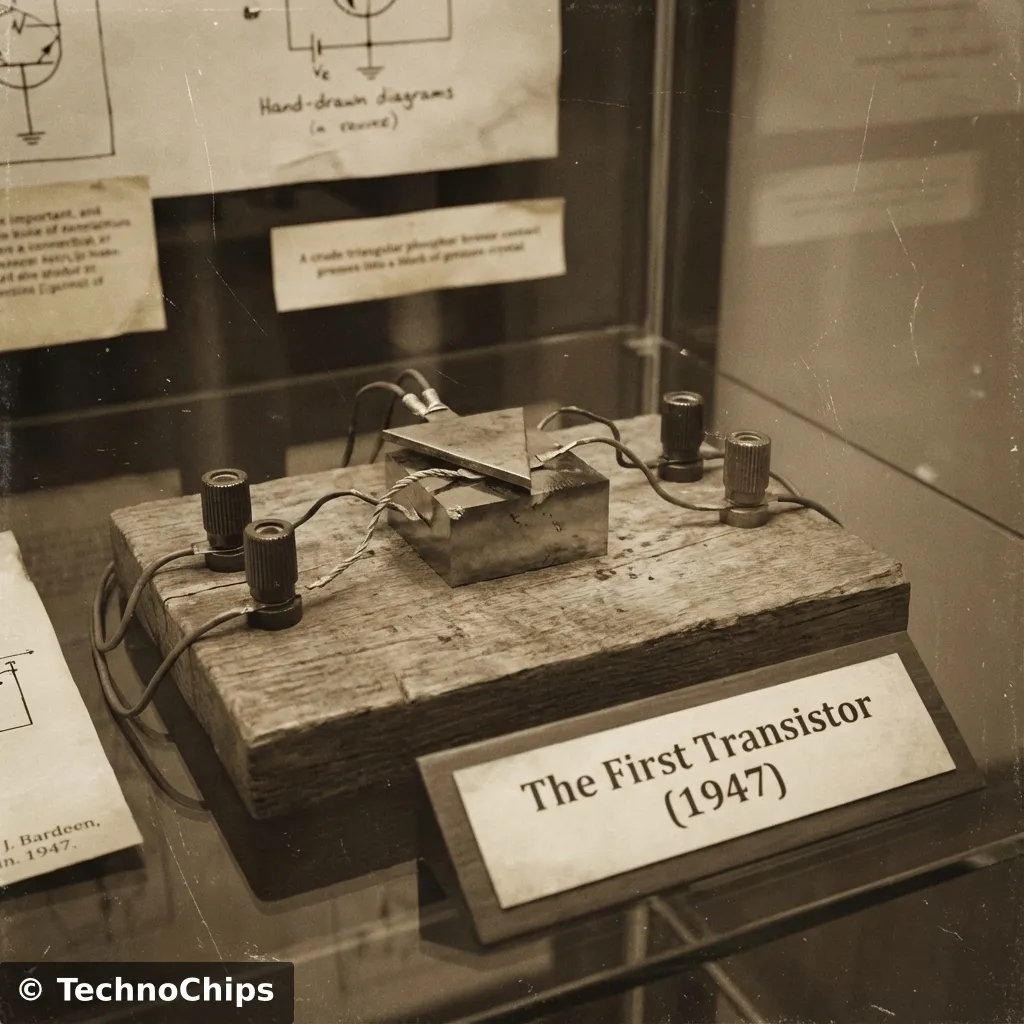

Before transistors, we had Vacuum Tubes. They were the size of lightbulbs, hot, fragile, and consumed massive power. The first computer (ENIAC) had 18,000 tubes and filled a room. At Bell Labs in 1947, Shockley, Bardeen, and Brattain invented the point-contact transistor. It looked like a piece of trash. A paperclip pressing onto a germanium block. But it worked. They won the Nobel Prize. And they gave us the modern world.

Gordon Moore, a co-founder of Intel, noticed a trend in 1965. “The number of transistors on a chip doubles every two years.” He was right.

| Feature | BJT (2N2222) | MOSFET (IRLZ44N) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Current (Base) | Voltage (Gate) |

| Switching Speed | Fast | Ultra Fast |

| Heat | Wastes power | Very Efficient |

| Usage | Small signals | Big Power |

| Symbol | Arrow on Emitter | Gap in line |

Working with these tiny three-legged beasts requires some finesse.

I want you to pause and look at your simple LED circuit. You touch the wire. The light turns on. You just controlled a flow of electrons using nothing but your presence. The component you just used—the 2N2222—costs $0.02. Yet, it is the same fundamental machine that calculates the trajectory of rockets, renders your video games, and processes the AI writing this very sentence. You have mastered the “Bit”. The “1” and the “0”. You are now speaking the language of computers.

Here is a puzzle for you. Can you wire a circuit so that when you touch the button ONCE, the LED stays ON forever? (Hint: You need to feed the output of the transistor back into its own Base). This is called a “Latch” or a “Thyristor” effect. Give it a try. If you figure it out, you just invented computer memory (SRAM).

We have resistors (Friction), Capacitors (Springs), and Transistors (Valves). Tomorrow, we learn about The Clock. How do computers minimize time? We will meet the 555 Timer, the heartbeat of electronics.

Q: Can I use a 2N3904 instead of 2N2222? A: Yes! They are almost identical for hobby circuits. Just check the pinout to be sure.

Q: Why do we need a resistor on the Base? A: To protect the transistor! The Base-Emitter path is basically a diode. If you connect it directly to 9V, infinite current flows and the transistor explodes. Always use a resistor (1kΩ or 10kΩ).

Q: My Touch Switch turns on when I just wave my hand near it! A: Congratulations, you built an antennae. Your body acts as a capacitor coupling 60Hz mains hum from the walls into the sensitive base.

Q: What is a MOSFET? A: It’s a modern type of transistor. NPNs are controlled by Current. MOSFETs are controlled by Voltage. MOSFETs are what CPUs are made of because they are more efficient.

Q: Can I control a motor with this? A: Yes! But motors create “Flyback Voltage” when they stop spinning, which can kill the transistor. You need a “Flyback Diode” to protect it. We will cover this later.