The Great Restrictor: Mastering Resistance & Ohm's Law

Stop burning out your LEDs. Master electrical resistance, Ohm's Law calculations, and build your first protected circuit in Day 3 of our Electronics series.

Read More →

* SYSTEM.NOTICE: Affiliate links support continued laboratory research.

Welcome to Day 2 of the 75-Day Master Analog Electronics Course. Yesterday, we conquered Voltage—the potential, the pressure, the hill. Today, we open the floodgates.

Voltage is the desire; Current is the action. Voltage is the cliff; Current is the falling rock. Without current, nothing happens. It is the lifeblood of every circuit, the physical movement of charge that actually does the work.

Whether it’s lighting up your screen, spinning a motor, or calculating a logic operation inside a CPU, it is the movement of electrons that makes it possible. You can have 1,000,000 Volts, but if no current flows, you have zero power.

In this deep dive, we are going to visualize, measure, and master the flow of electricity. We will debunk common myths about electron speed, learn why current kills, and discover how a tiny magnetic field can change the world.

Prepare to shift your mental model from “static pressure” to “dynamic flow.” This is where the magic of analog electronics truly begins.

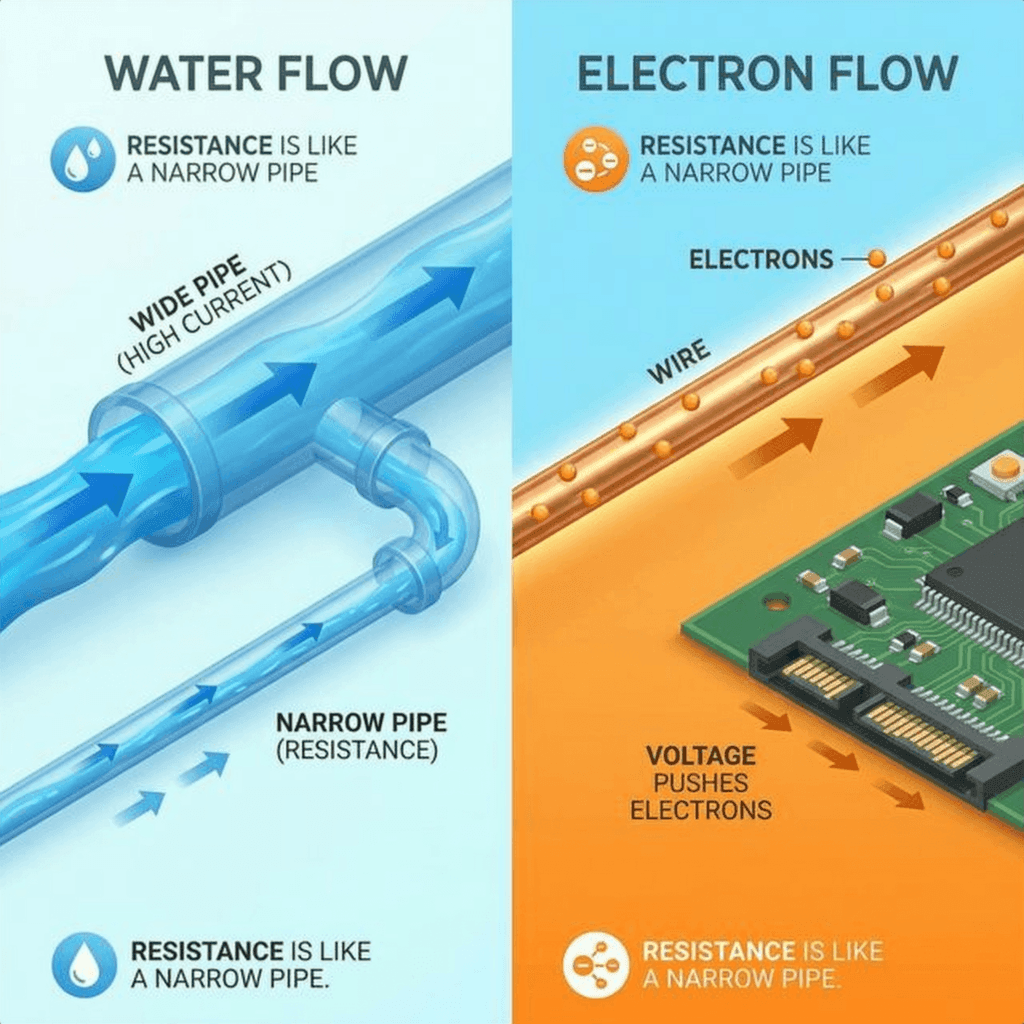

Current () is the rate of flow of electric charge. It is not the charge itself; it is the movement of that charge. If Voltage is the height of the water tower, Current is the gallons per minute rushing through the pipe.

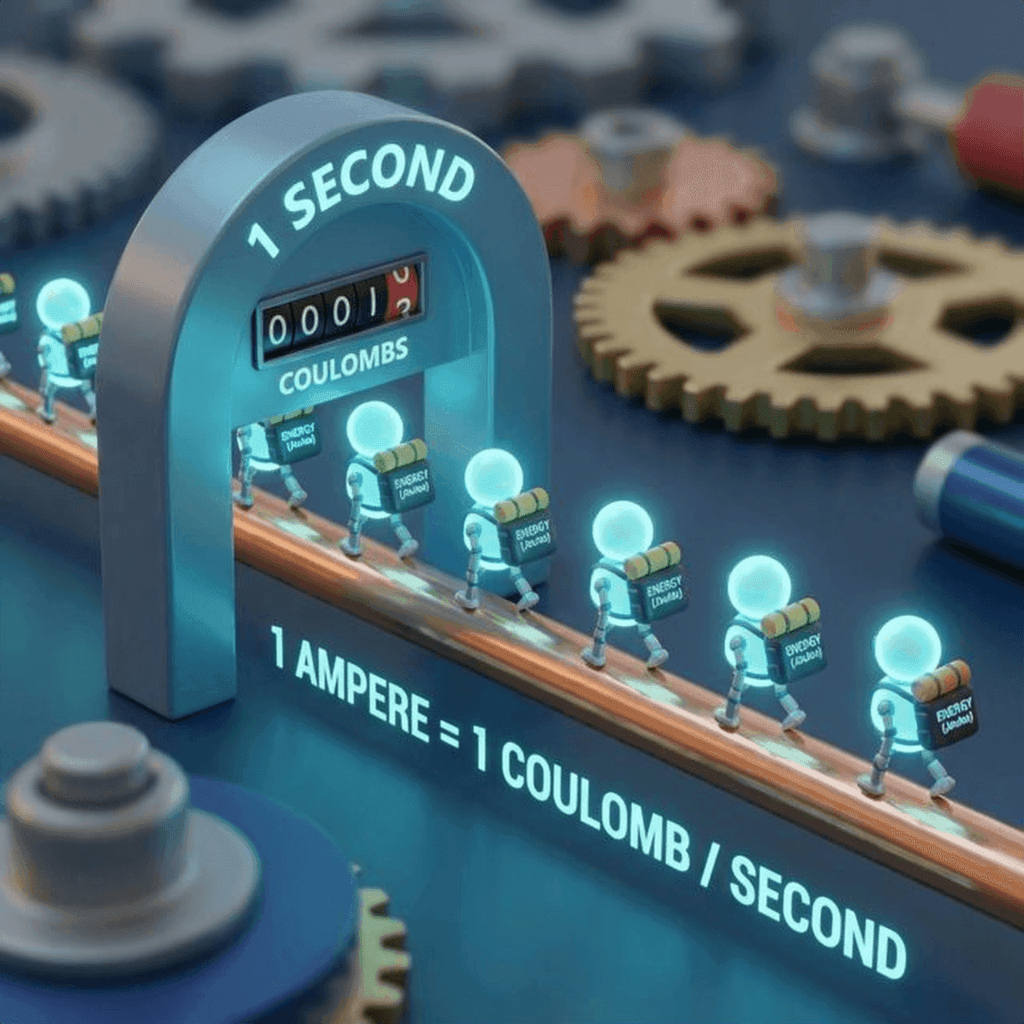

The unit of Current is the Ampere (A), named after André-Marie Ampère. One Ampere is defined as one Coulomb of charge passing a specific point in one second.

Think of a highway. The cars are the electrons (charge). The speed of the cars is the drift velocity. But “Current” is simply the count of how many cars pass under a bridge every second.

If traffic is jammed, current is low. If traffic is flying, current is high. In electronics, we control this flow with precision to perform miracles of engineering.

To truly grasp the Ampere, you must understand the Coulomb. A Coulomb is a bucket of charge—specifically, about electrons. That is 6 billion billion electrons.

When we say “1 Ampere,” we mean that one entire bucket of electrons is physically moving past a point in your wire every single second. That is a massive amount of material moving!

Imagine a line of hikers each wearing a backpack. The backpack represents the charge (). The hikers are the electrons. Current is just a measure of how many backpacks cross the finish line per second.

If the hikers run faster (higher voltage pressure), the current increases. If the path gets wider (lower resistance), more hikers can walk side-by-side, and current increases. This is the fundamental physical reality of circuitry.

Here is a fact that blows every beginner’s mind: Electrons are incredibly slow.

When you flip a light switch, the light turns on instantly. You assume the electrons rushed from the switch to the bulb at the speed of light. They didn’t. They barely moved 1 millimeter.

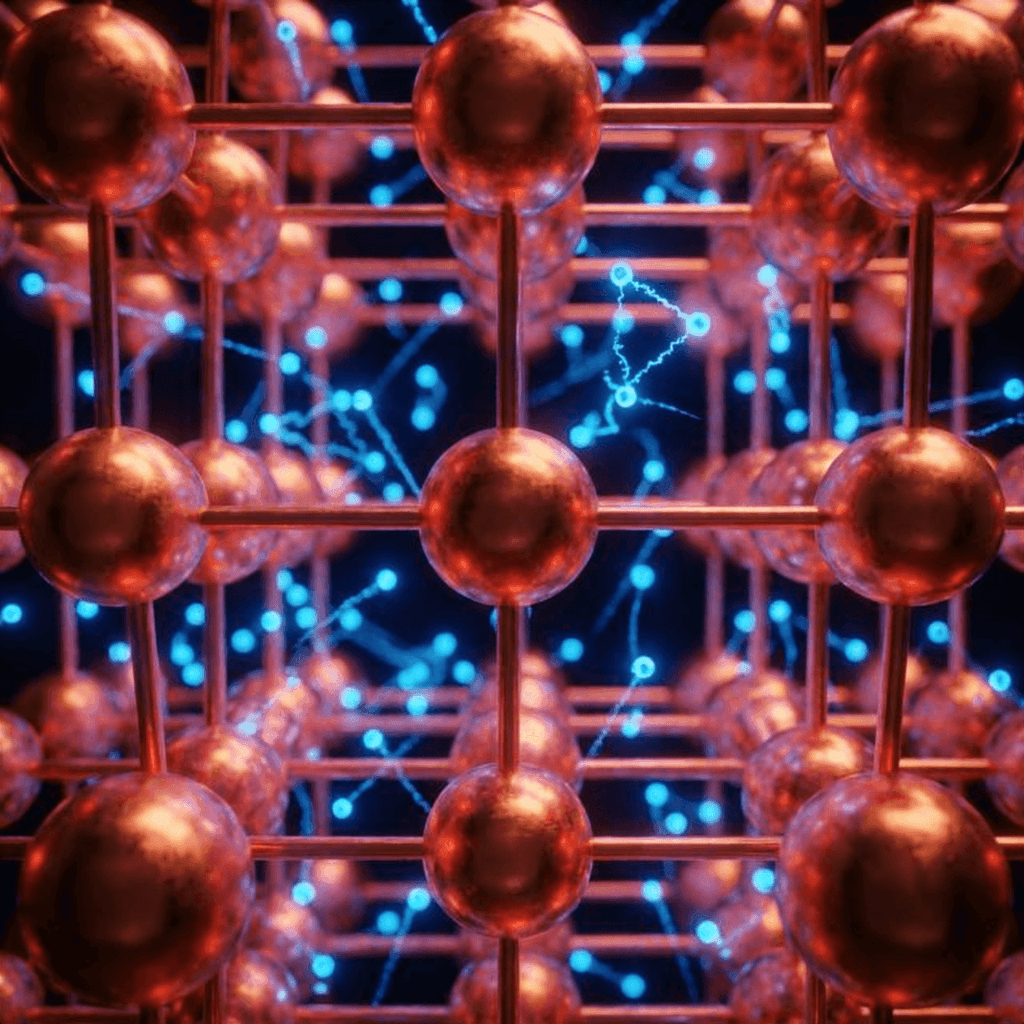

This is called Drift Velocity. In a standard copper wire carrying 1 Amp, the actual physical electrons are crawling along at about 0.02 mm per second. A snail is faster!

So why is the light instant? Because the Electric Field moves at near light speed. Think of a tube filled with marbles (electrons). If you push a marble in one end, a marble pops out the other end instantly.

The “push” wave travels fast, but the individual marbles move slow. Your voice travels at the speed of sound, but the air molecules coming out of your mouth don’t reach the listener’s ear. It’s the wave that carries the energy, not the particle itself.

This is the “Golden Rule” of electronics. Current requires a closed loop. It must have a path out of the source, through the load, and back to the source.

If you cut the wire anywhere, the current stops everywhere instantly. It doesn’t “leak out” the end of the cut wire. The electric field collapses, and the push disappears.

This is why birds can sit on power lines. They are not touching the ground, so there is no loop. The current has no reason to go through the bird when the copper wire offers a much easier path.

However, if that bird touches the pole and the wire at the same time… ZAP. The loop is closed, and current flows. Always look for the return path. Ground is usually that return path.

How do we measure current without cutting the wire? We use the Hall Effect. Discovered by Edwin Hall in 1879, this phenomenon is the basis of modern contactless current sensing.

When electrons flow through a conductor, they are moving charges. If you place a magnet perpendicular to this flow, the magnetic field exerts a “Lorentz Force” on the electrons, pushing them to one side of the conductor.

This pile-up of electrons creates a measurable voltage difference across the width of the conductor, known as the Hall Voltage (). By measuring this tiny voltage, we can calculate the current () without ever physically touching the electrons. This is how “Clamp Meters” work, allowing electricians to check high-current lines safely.

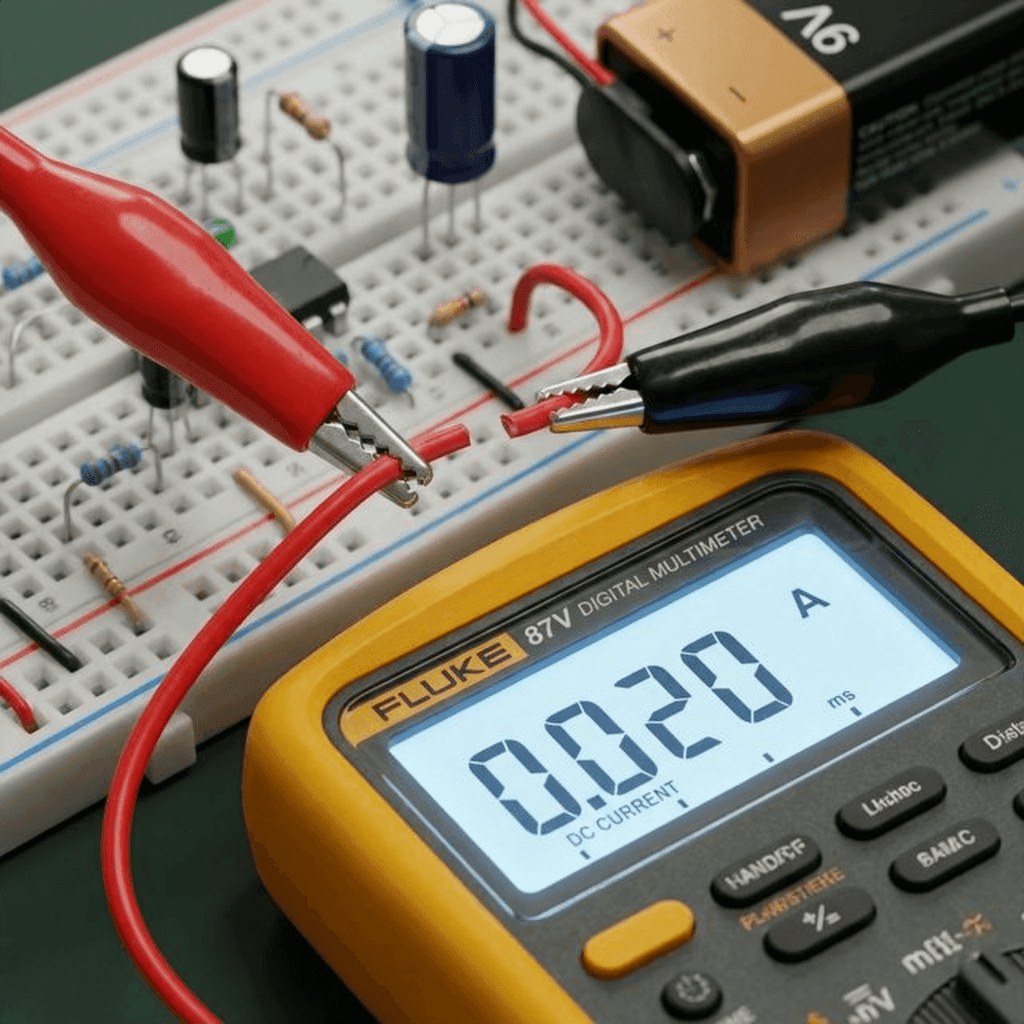

Measuring current is dangerous. Unlike voltage, where you just touch the probes to the circuit (Parallel), to measure current you must become part of the circuit (Series).

You must break the loop. You have to physically cut the wire and insert your multimeter in between. The current must flow through your meter.

Most multimeters have a 10A fuse and a 200mA fuse. If you try to measure a high current circuit on the low setting, you will blow the fuse instantly.

This is the most common mistake “newbies” make. They put the probes in parallel (like voltage) while in Current Mode. This creates a Short Circuit through the meter, blowing the fuse immediately.

Always start with the highest range (10A) and move the red probe to the “10A” jack. Only move down to mA if you are sure the current is low.

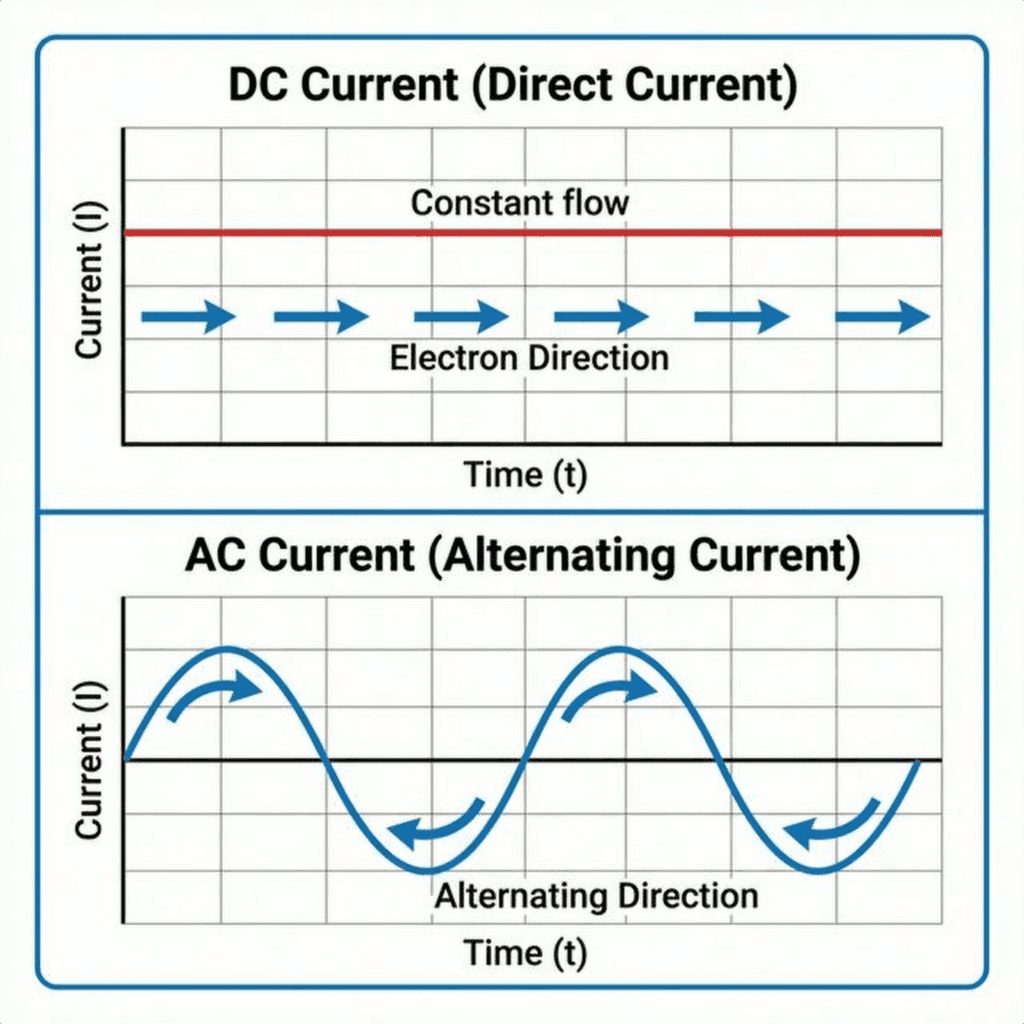

In the late 19th century, a fierce battle raged between Thomas Edison (DC) and Nikola Tesla (AC).

Direct Current (DC) flows in one river-like direction. It is great for batteries and electronics over short distances. Edison built DC power plants in NYC, but they could only send power a few miles before line losses () made the voltage too low to use.

Alternating Current (AC) wiggles back and forth. Tesla realized that with a Transformer, he could step up AC voltage to thousands of volts, drop the current to near zero, and transmit it hundreds of miles with almost no loss.

When it arrived at the city, another transformer stepped it back down to safe levels. Tesla won the war when he lit up the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and harnessed Niagara Falls in 1895. Today, our grid is AC, but our gadgets are DC.

Why 60Hz vs 50Hz? It was a compromise. Lower frequencies (30Hz) caused light bulbs to flicker visibly. Higher frequencies (133Hz) caused too much line loss. Westinghouse settled on 60Hz for the US, while AEG in Germany chose 50Hz for Europe.

In DC, current uses the entire cross-section of the wire. But in high-frequency AC, something strange happens. The changing magnetic fields inside the wire push the electrons toward the surface.

This is called the Skin Effect. At high frequencies (like in radio transmitters or switching power supplies), the center of the wire carries almost no current at all!

This increases the effective resistance of the wire. This is why high-frequency Litz wire is made of thousands of tiny insulated strands woven together—to increase the total surface area and reduced the AC resistance.

When current goes where it shouldn’t, bad things happen.

A short occurs when the resistance in the loop drops to near zero. According to Ohm’s Law (), if is zero, becomes infinite.

Infinite current means infinite heat. Wires melt, batteries explode, and houses burn down. This is why we never, ever connect the positive and negative terminals of a battery directly together.

An open is a broken loop. Infinite resistance. Zero current. This is safe, but your device stops working. A blown fuse acts as an intentional open circuit to save the day.

This is when current finds a “sneak path” it shouldn’t, usually through moisture, dirt, or poor insulation. This can drain batteries or cause GFCI breakers to trip in your bathroom.

It’s not just total amps that matter; it’s Current Density (). Current density is amps per unit area. You can push 10A through a thick cable, but if you try to push 10A through a tiny PCB trace, the density is too high. The trace will heat up, delaminate from the board, and burn open. PCB designers use standard tables (IPC-2221) to calculate the required trace width for a given current. A standard external 1oz copper trace needs about 12mils (0.3mm) of width for every 1A of current to keep temperature rise acceptable.

You’ve heard “It’s not the volts, it’s the amps.” This is technically true but misleading. You need high voltage to push the current through human skin.

Your dry skin has about resistance. A 9V battery can’t push enough current to hurt you. But 120V from the wall can push easily.

Always respect the current. Keep one hand in your pocket when working with high voltage to prevent a path across your heart.

A fuse is a guardian. It is a thin piece of wire designed to be the “weakest link.” If the current exceeds a safe limit (say, 2 Amps), the fuse wire melts and physically breaks the circuit.

It sacrifices itself to save your expensive electronics (and your house). Never bypass a fuse with a piece of wire (“jumping the fuse”). That is a recipe for a fire. Always replace a fuse with one of the exact same rating.

Slow-Blow vs Fast-Blow: Some fuses pop instantly (Fast). Others wait a second to handle “inrush current” from motors starting up (Slow). Using the wrong type can cause nuisance trips or dangerous delays.

Current doesn’t have to be sustained to cause damage. A tiny spark from your finger when you touch a doorknob involves thousands of volts, but extremely low current. However, for a silicon chip, this tiny current spike is enough to punch a microscopic hole in the transistor gates, destroying the device instantly. This is called ESD Damage. Professional labs use grounded wrist straps and conductive mats to provide a safe path for this static current to flow to ground, bypassing sensitive components entirely.

Here is the secret connection: Moving Charge Creates a Magnetic Field.

In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted noticed a compass needle twitch when he turned on a battery circuit nearby. He discovered that electricity and magnetism are two sides of the same coin.

Every wire carrying current has a magnetic field swirling around it (Right-Hand Rule). If you coil the wire, the fields add up to create a powerful Electromagnet.

This is how motors, speakers, relays, and transformers work. Without current, we have no magnetism. Without magnetism, we have no modern motion or power grid.

A lightning bolt is the ultimate example of current. It is a massive electrostatic discharge between the clouds and the ground. A typical bolt carries 30,000 Amps at millions of volts. The air, which is normally an insulator, breaks down into plasma, creating a conductive channel. The temperature of this channel reaches 30,000 Kelvin—five times hotter than the surface of the sun. The sudden expansion of air causes the thunderclap.

A solar panel acts like a variable current source. The more photons that hit the precise silicon lattice, the more electron-hole pairs are created, and the more current flows. Unlike a battery, if you short-circuit a solar panel, it doesn’t explode. It simply delivers its maximum Short Circuit Current (). The voltage drops to zero, so power is zero (), and surprisingly little heat is generated.

The US Navy has experimented with Railguns, which use massive currents (millions of amps) to accelerate a projectile to Mach 7. The current flows up one rail, through the projectile, and down the other rail. The magnetic field created by this massive loop interacts with the current itself, generating a Lorentzian force that pushes the projectile forward at hypersonic speeds. No explosives required—just raw amps.

We measure energy storage in Amp-Hours (Ah). If a battery is rated for 2000mAh (2Ah), it theoretically can provide:

However, in reality, due to the Peukert Effect, drawing current faster reduces the total capacity available. A lead-acid battery drained in 1 hour might only give you 60% of its rated energy, while draining it over 20 hours gives you 100%.

Gustav Kirchhoff gave us another law: Current In = Current Out.

At any junction (node) in a circuit, charge cannot pile up or vanish. The sum of currents entering a node must equal the sum of currents leaving it. If you have 10A flowing into a splitter, and 3A goes left, then 7A must go right. This is Conservation of Charge. It is the basis for analyzing complex parallel circuits and understanding how power is distributed in your home.

Just as voltage divides in series, current divides in parallel. If you have two resistors in parallel (), the current splits based on the ratio of conductances. The larger current always takes the path of least resistance. Mastering this intuition helps you spot “current hogs” in your designs without doing full math every time.

How do we measure massive currents, like 1000A in a substation? We use a Current Transformer. It is a donut-shaped transformer that steps down the current. A 1000:5 CT turns 1000A on the primary wire into a manageable 5A on the secondary for measurement. A key safety rule: NEVER open-circuit a live CT secondary. It will generate infinite voltage trying to push that current, causing an arc flash explosion.

Why do phone chargers get hot? Why do CPUs need fans? It’s Joule Heating. Power loss in a wire is defined as . This is critical.

Notice the Square. If you double the current, the heat goes up by four times. If you triple the current, the heat goes up by nine times!

This is why we transmit power at high voltage and low current. 10 Amps is 100 times harder to manage thermally than 1 Amp. High current melts connectors, burns PCB traces, and destroys efficiency.

In a resistor, current is simple (). But with reactive components, time matters.

In 1900, Paul Drude proposed that electrons bounce around like gas molecules. When an electric field is applied, they gain a net drift velocity. While modern Quantum Mechanics has refined this, the Drude model is surprisingly accurate for understanding basic conductivity and Ohm’s Law in simple metals.

When two different metals (like copper and aluminum) touch in the presence of moisture (an electrolyte), a tiny current flows between them due to their different electrode potentials. This current causes Galvanic Corrosion, eating away the anode metal. This is why you never use copper wire with aluminum connectors without a special anti-oxidant grease.

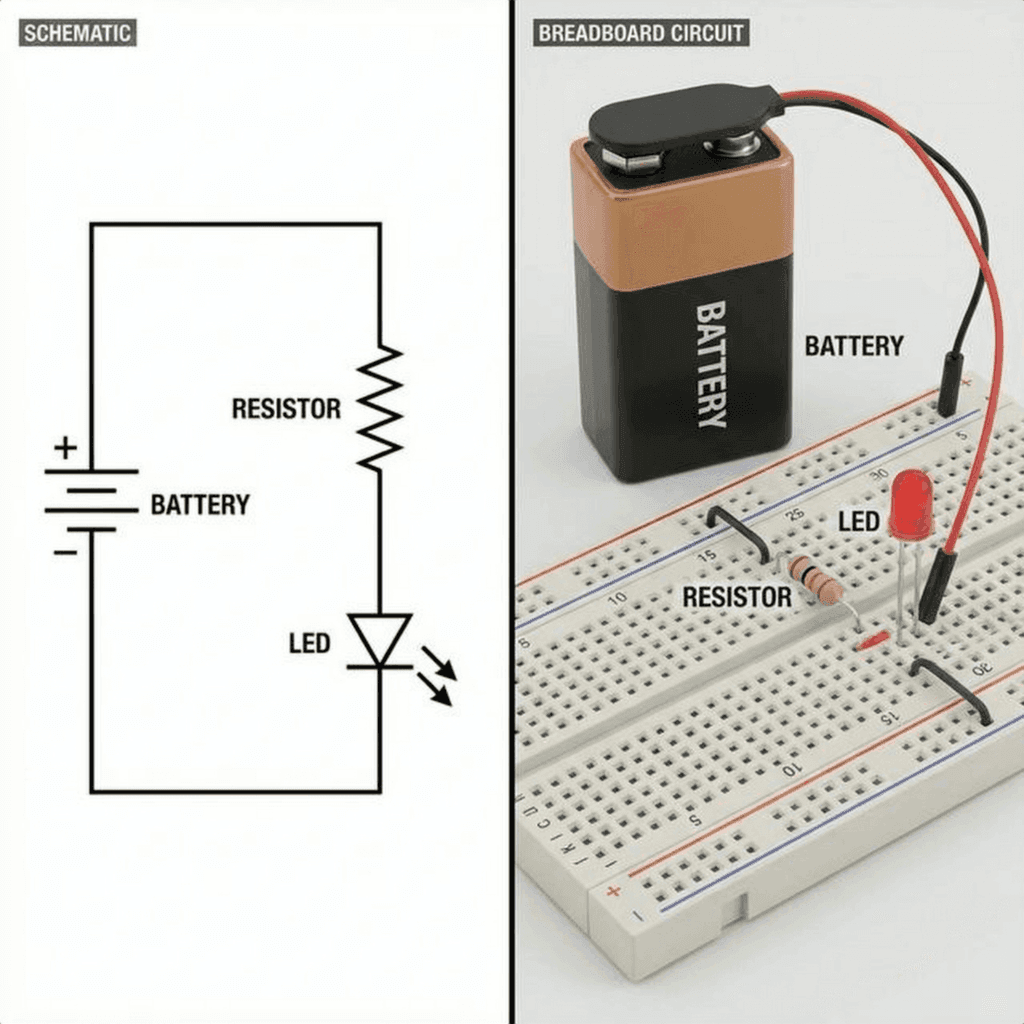

In a Resistor, current is Linear (). In a Diode, current is Exponential (). This means that below 0.7V (Silicon), almost no current flows. But once you cross 0.7V, current shoots up uncontrollably. This is why you MUST always use a current-limiting resistor with an LED. Without it, the “exponential cliff” will destroy the diode in milliseconds.

If you dip two electrodes in a gold chloride solution and pass current, gold ions move to the cathode and deposit a thin layer of pure gold. This is Electroplating. The thickness depends precisely on Current Time. Jewelry, PCBs, and even car bumpers rely on this controlled current flow for their finish.

Some crystals (like Quartz) generate current when squeezed. This is called Piezoelectricity. It works in reverse too: apply current, and the crystal vibrates. This is the heart of every quartz watch, keeping time by vibrating exactly 32,768 times per second.

Why 32,768 Hz? It is . A simple digital counter can divide this frequency by two, fifteen times, to get exactly one steady pulse per second (1 Hz). Unlike a resistor-capacitor timer which drifts with temperature, a quartz crystal’s mechanical vibration is incredibly stable. It ensures that your digital clock doesn’t lose minutes every day. This proves that mechanical current resonance is the heartbeat of the digital world. Without this tiny crystal kicking current back and forth, modern CPUs would drift and crash instantly.

Before silicon, we used Vacuum Tubes. A hot filament boiled electrons off a cathode into a vacuum. A high-voltage plate attracted them, creating current flow through nothingness. Since there are no atoms to bump into, these electrons can move incredibly fast. This is why high-end audiophiles and guitar players still love tubes—the way current flows through a vacuum creates a warm, unique distortion that solid-state transistors struggle to replicate.

By placing a mesh grid between the cathode and plate, we can control this massive flow with a tiny voltage. This was the first true amplifier, launching the age of radio, television, and widely available consumer electronics.

A battery is a Voltage Source—it tries to keep voltage constant. A Current Source tries to keep current constant.

We build these using transistors. LED drivers are current sources. An LED creates light based on current, not voltage. If you give an LED precise 20mA, it glows perfectly. If you try to force 3V across it without limiting current, thermal runaway occurs, and it burns out.

Understanding the difference between controlling voltage (Force) and controlling current (Flow) is the mark of a true analog designer.

What if resistance was zero? In certain materials cooled to near absolute zero, current can flow forever without stopping. This is Superconductivity.

In an MRI machine, the massive magnets are superconducting coils. Once the current is started, it will circulate for years without a battery, creating a perfect, stable magnetic field. This is the ultimate expression of “Current without Pressure drop.”

| Material | Conductivity () | Resistivity () | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver | Best conductor, expensive contacts | ||

| Copper | Standard wiring | ||

| Gold | Corrosion-resistant connectors | ||

| Aluminum | High-power transmission lines | ||

| Iron | Poor conductor, used in transformer cores |

| AWG Size | Diameter (mm) | Max Amps (Chassis) | Max Amps (Power Transmission) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 AWG | 2.588 | 55A | 15A |

| 12 AWG | 2.053 | 41A | 9.3A |

| 14 AWG | 1.628 | 32A | 5.9A |

| 18 AWG | 1.024 | 16A | 2.3A |

| 22 AWG | 0.644 | 7A | 0.92A |

| 28 AWG | 0.321 | 1.4A | 0.22A |

JST-XH: The white connectors on batteries. Rated for 3A. Dupont (Breadboard): The thin jumper wires. Rated for roughly 1A. XT-60: The yellow connectors on drones. Rated for 60A. USB-C: Can handle 5A with an E-Marked cable. Barrel Jack (DC): Typical 2.1mm CCTV plug. Rated for 5A max.

Let’s prove the relationship between Resistance and Current.

Why? Lower resistance allowed more flow (Current). More electron flow means more photon collisions inside the LED semiconductor, resulting in more light output. You just controlled physical reality with a resistor.

Current is the worker bee of electronics. It is the physical transport of energy. You learned that it is slow (drift velocity) but powerful ().

Homework Challenge:

Q: Can I measure current without cutting the wire? A: Yes, but you need a “Clamp Meter” which detects the magnetic field. Q: Why does my battery get hot when I short it? A: Chemical energy is being converted to heat inside the battery’s internal resistance. Q: Is 1 Amp a lot? A: It depends. For an LED, it’s instant death. For a car starter motor, it’s nothing (they use 200A+). Q: Does current get “used up”? A: No! The current entering a resistor is exactly the same as the current leaving it. Energy is used, charge is conserved.