The Component That Changed History: Master the Transistor & Build a Touch Switch

From sand to supercomputers. Learn how the NPN transistor works, why it is the most important invention in history, and build a circuit controlled by your finger.

Welcome back to Day 2.

Yesterday, we faced our fears. Today, we face the physics.

But don’t panic. We aren’t going to use boring textbook definitions. We aren’t going to talk about “Coulombs of charge” or “Potential difference between two points in an electrostatic field.”

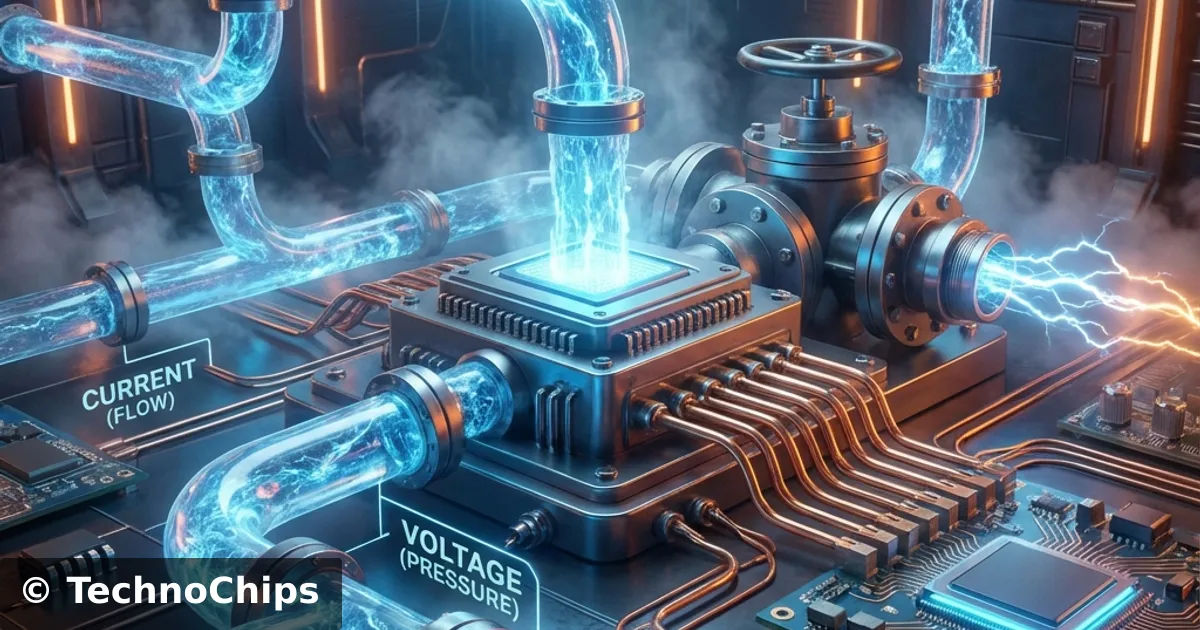

We are going to talk about Water.

Why? Because electricity is invisible. You can’t see it flowing (unless something has gone terribly wrong). This makes it incredibly hard to visualize. Water, on the other hand, we understand instinctively. We know that water falls down. We know that high pressure sprays harder. We know that a thin pipe flows slower than a fat pipe.

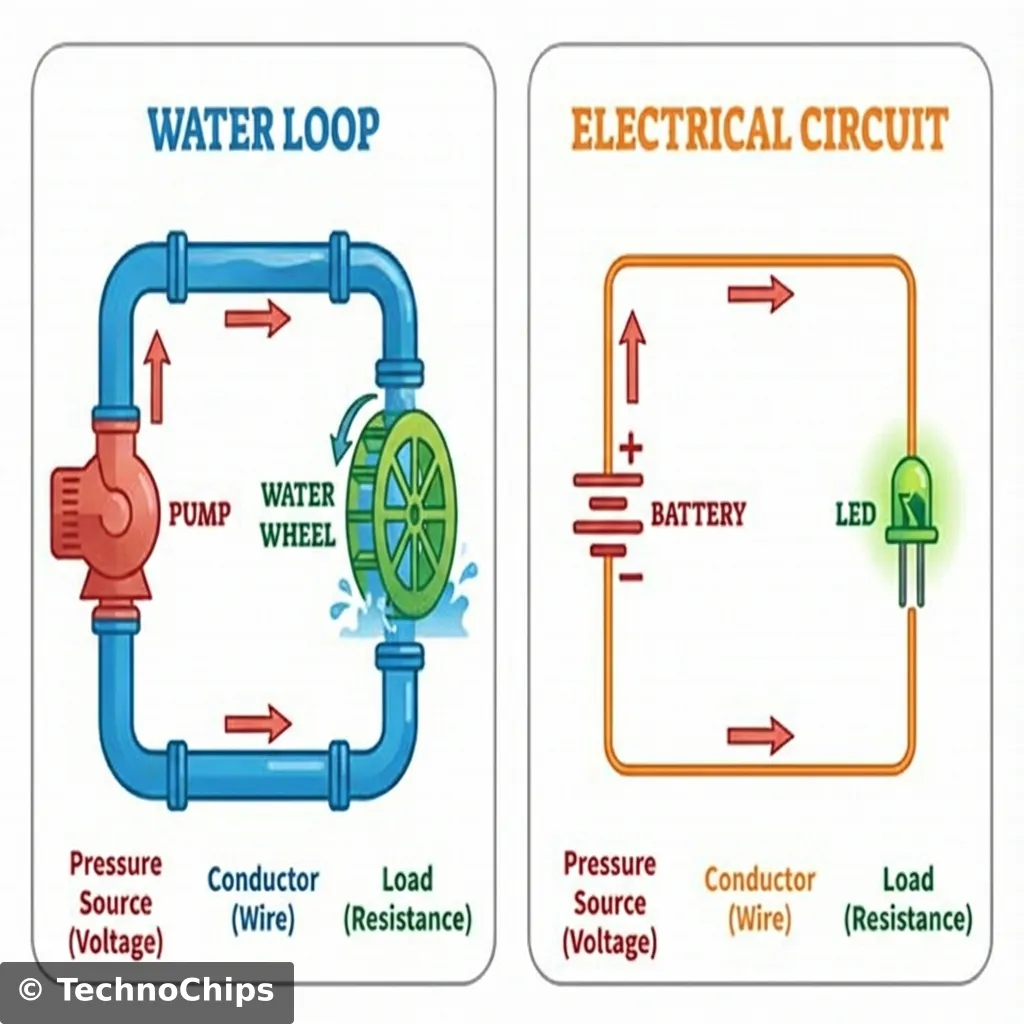

Remarkably, electricity behaves almost exactly the same way as water. This is known as the Hydraulic Analogy, and it is the single most powerful tool you will ever have for understanding circuits.

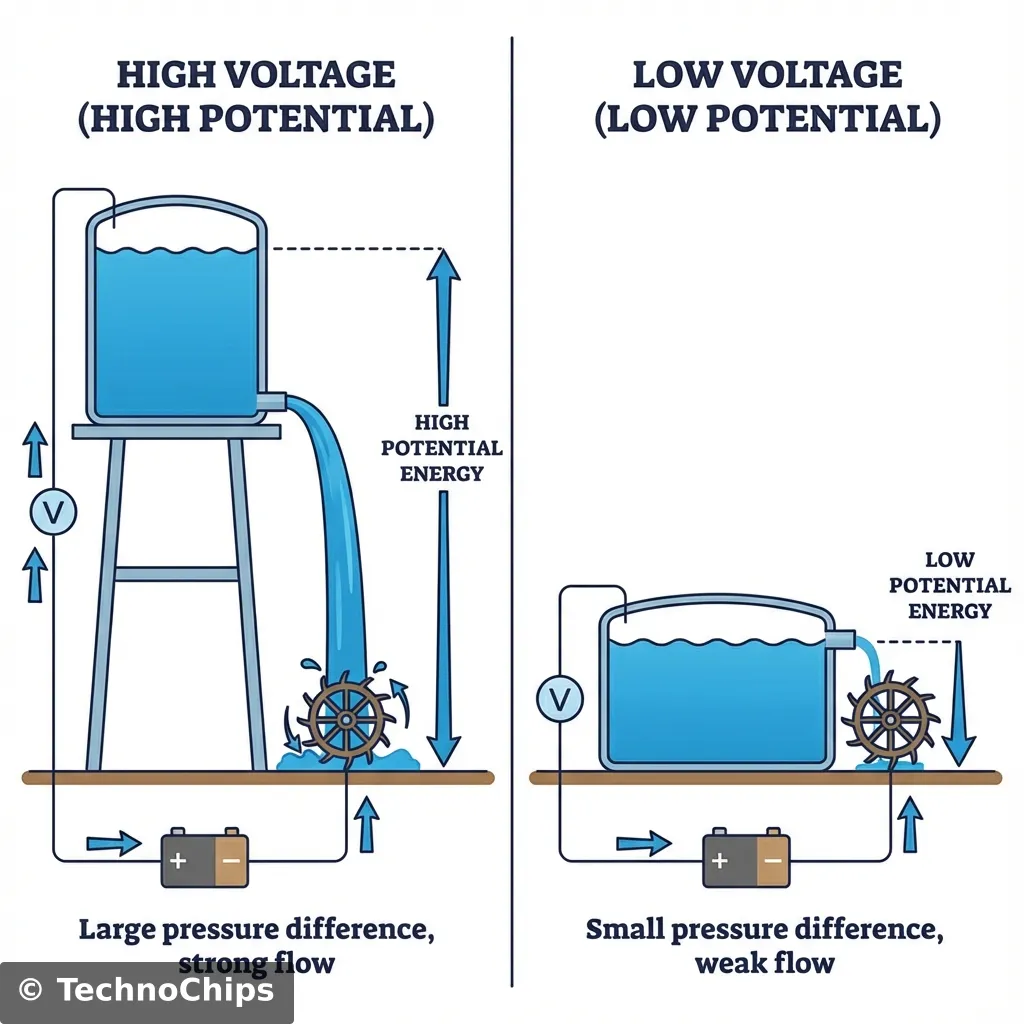

Imagine a large tank of water sitting on the ground. Now, imagine a second tank sitting on top of a 10-story building.

If you poke a hole at the bottom of both tanks, which one sprays water harder? Obviously, the one on the tower. Why? Because gravity is pulling down on that water column, creating Pressure.

In electronics, Voltage is that Pressure.

You will often hear Voltage called “Potential Difference.” Look at the tank again. The pressure exists because there is a difference in height between the top of the water and the ground. If you have a pipe connecting two tanks that are at the exact same height, does water flow? No. Because there is no difference in pressure.

This is why birds can sit on power lines without getting shocked. They are touching 10,000 Volts, but their entire body is at 10,000 Volts. There is no difference across their body. But if they touched the wire (10,000V) and the pole (0V Ground) at the same time? ZAP. The pressure difference creates flow.

Voltage (V) is the desire of electrons to move.

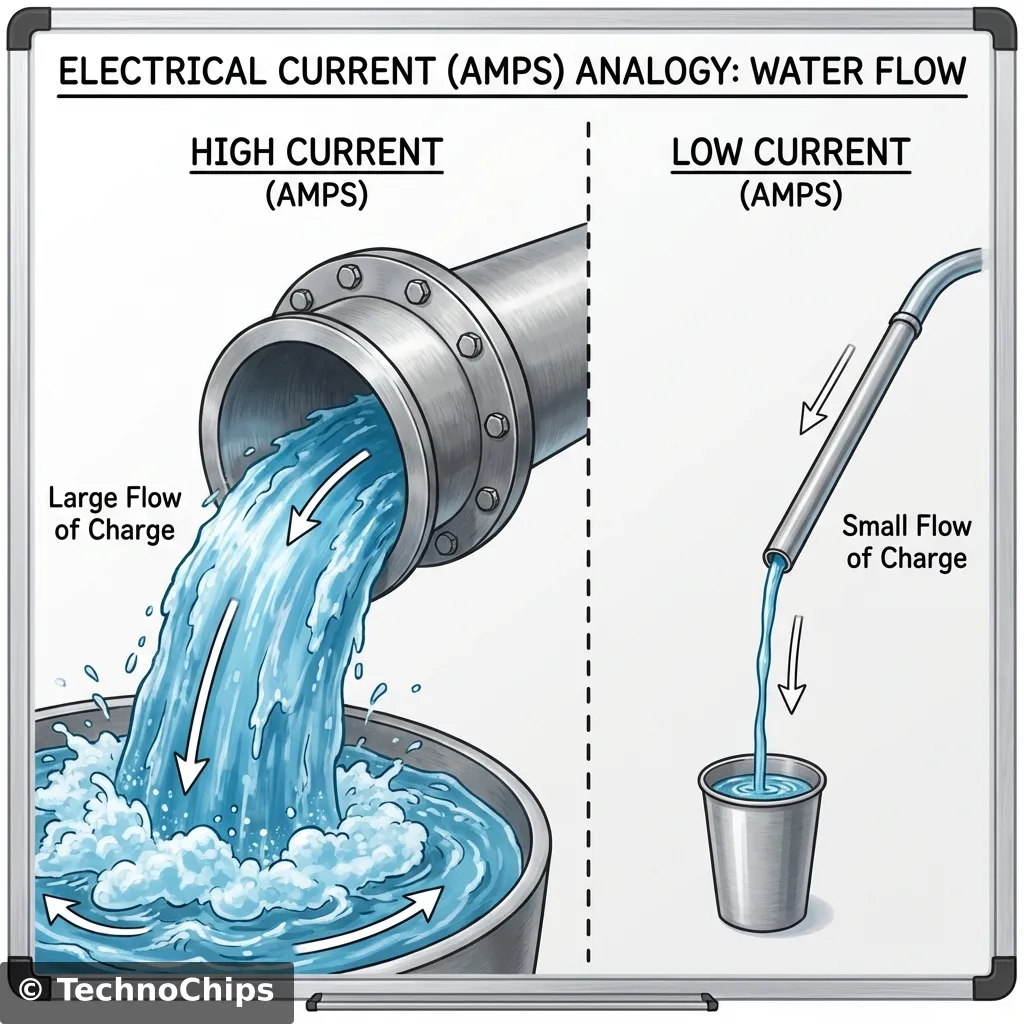

Now we have pressure. But pressure alone doesn’t do any work. A pressurized tank with the valve closed is just potential energy waiting to happen. To get work done, we need movement. We need Flow.

If you attach a pipe to the tank and open the valve, water wets the ground. The amount of water that comes out every second is the Current.

You cannot have Current without Voltage (Pressure), just like you can’t have water flow without gravity/pumps. But you can have Voltage without Current (like a battery sitting on a shelf).

Current (I) is the actual movement of electrons doing the work.

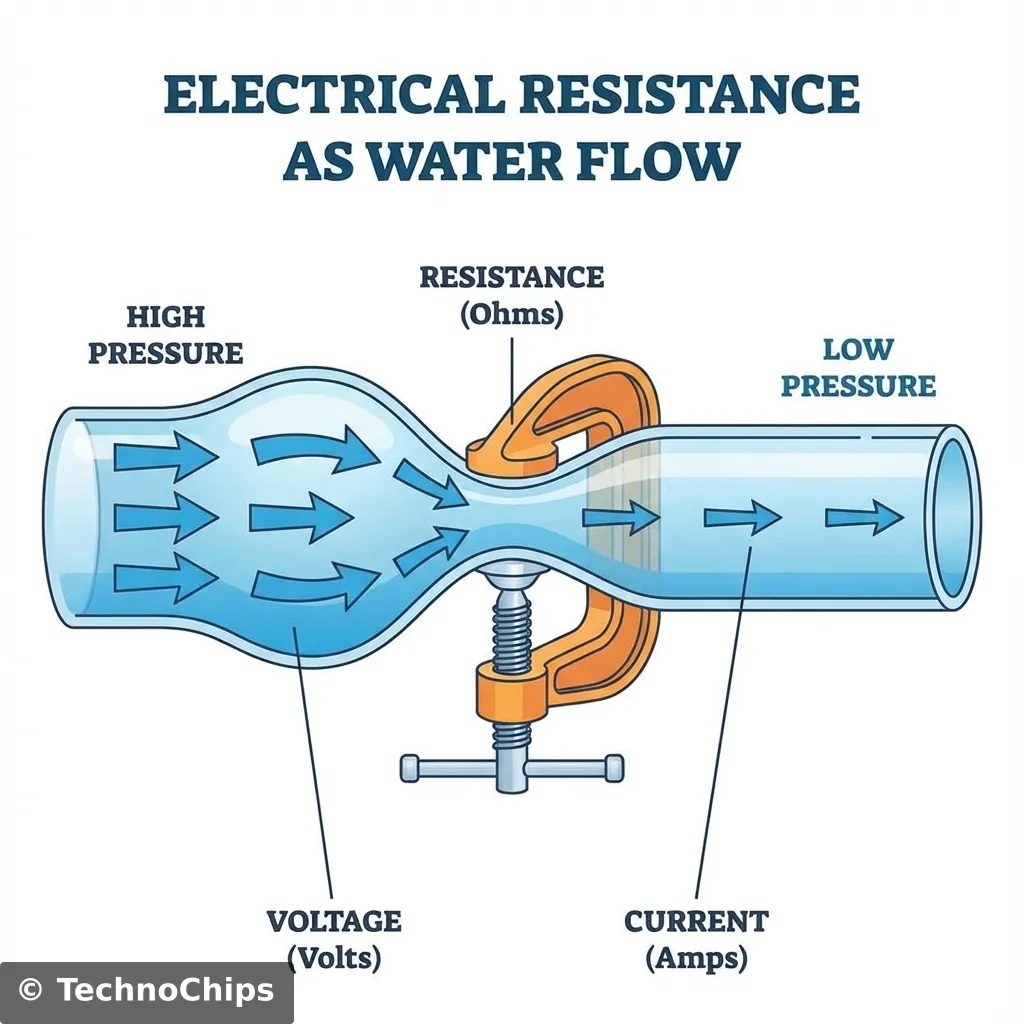

So we have a high tank (Voltage) and a pipe (Current). How do we control the flow? If we just let the water run freely, the tank empties in seconds. That’s a short circuit. We need to throttle it.

Imagine we stuff the pipe full of sand, or squeeze it with a clamp. What happens? The water has to fight its way through the constriction. The flow slows down.

This is Resistance.

Resistance (R) is how hard it is for Current to flow.

I promised no hard math, but this one equation is the E=mc² of electronics. It is simple, and it governs everything.

Voltage = Current × Resistance (V = I × R)

Let’s look at it in three ways:

V = I × R

I = V / R

R = V / I

Let’s use this theory to actually design something.

The Goal: We want to light up a Red LED. The Facts:

The Solution: We need a Resistor. We need to add a “restriction” in the pipe to eat up that extra pressure.

The Math (Ohm’s Law):

So, if we put a 350 Ohm resistor in the circuit, it creates just enough “friction” to slow the current down to a safe level. The LED glows happily. The resistor gets slightly warm (dissipating the energy).

This is Engineering. Using math to predict the future.

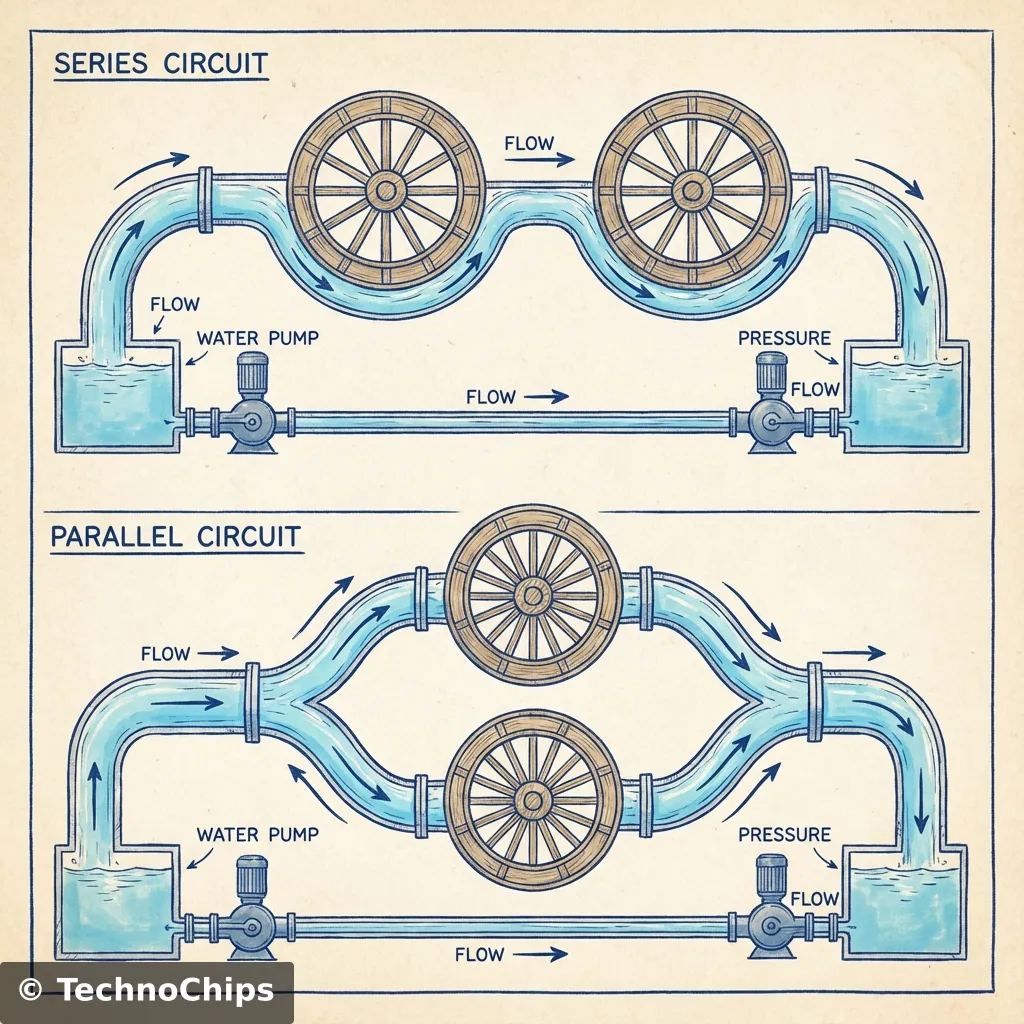

There are two ways to connect pipes.

Imagine two water wheels placed one after another in the same pipe.

Imagine a main pipe that splits into two branches, like a river forking.

One concept that confuses beginners is the “Circuit”. For electricity to flow, it must have a return path.

Water can just spray onto the ground and float away. Electrons cannot. They must return to where they came from (the Battery). If you cut the return wire, the flow stops instantly. This is an Open Circuit.

Think of the battery not as a storage tank, but as a Pump. A pump circulates water. It pulls water in one side and pushes it out the other. If you block the inlet, the outlet stops pushing. The circle of life must be unbroken.

As useful as this analogy is, it is not perfect. If you take it too literally, you might get confused later. Here is where it breaks down:

You will often see devices rated in Watts (e.g., a 100 Watt Bulb). Power (P) is the total work being done. It is a combination of both Pressure and Flow.

Power = Voltage × Current (P = V × I)

In our water analogy, Power is how fast the water wheel spins. A tiny stream at high pressure can spin it fast. A huge river at low pressure can also spin it fast. Both together spin it furiously.

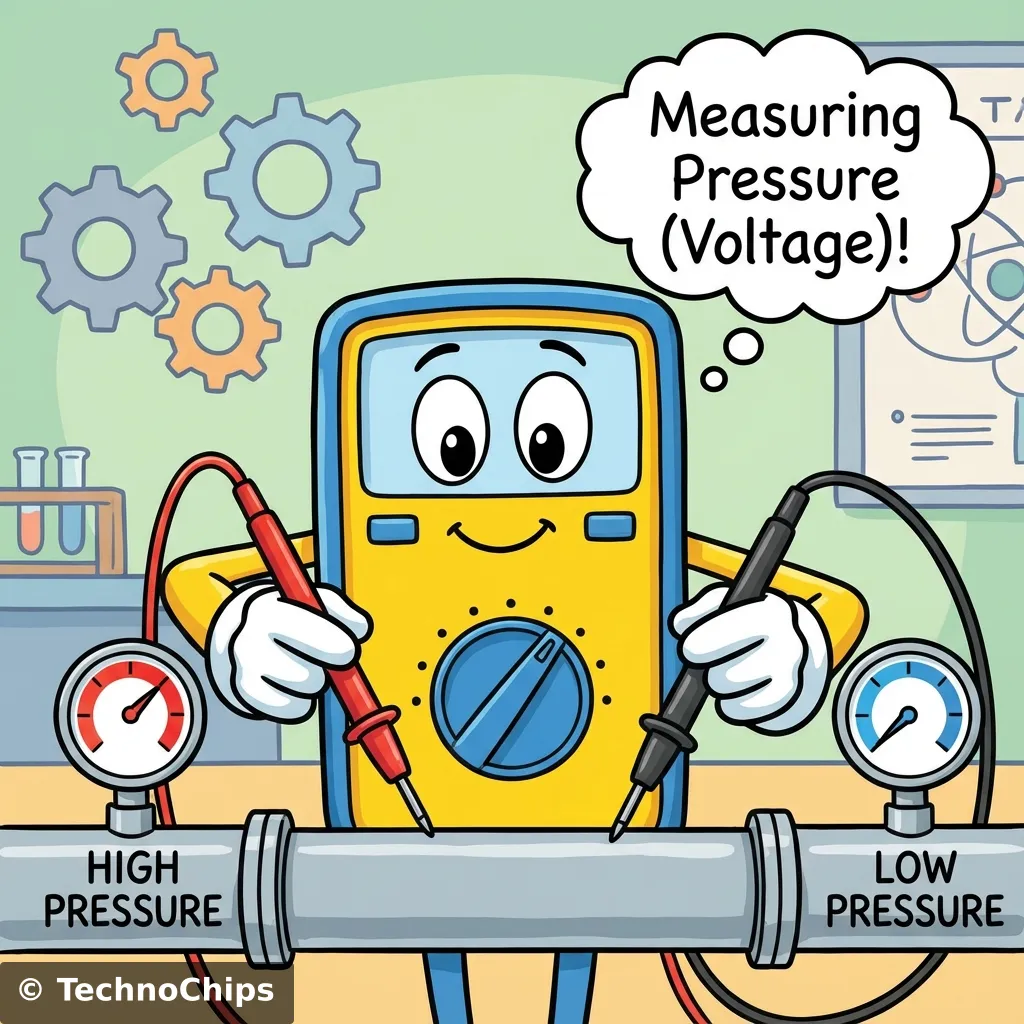

Since we can’t see electrons, we need eyes. That’s the Multimeter. A standard meter has three main modes:

Voltmeter Mode (V):

Ohmmeter Mode (Ω):

Ammeter Mode (A):

Here is your quick reference guide for translating between worlds.

| Concept | Electronics Name | Symbol | Unit | Water Analogy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Push | Voltage | V | Volts (V) | Water Pressure (Gravity/Pump) |

| Flow | Current | I | Amps (A) | Water Current (Volume/Sec) |

| Friction | Resistance | R | Ohms (Ω) | Pipe Width / Clogged Pipe |

| Source | Battery | DC | Volts | Water Pump / Water Tower |

| Load | LED / Motor | - | Watts | Water Wheel / Turbine |

| Control | Switch | - | - | Valve / Tap |

| Reference | Ground | GND | 0V | Sea Level / Drain |

When your circuit doesn’t work, visualize the water.

Problem: LED didn’t turn on.

Problem: LED flashed once and died.

Problem: Battery gets really hot.

Georg Simon Ohm was a German physicist in the 1820s. Ironically, when he first published his theory, he was ridiculed. The scientific establishment of the time thought his math was too simple to be true. They ignored him for nearly 20 years. Today, he is immortalized on every resistor in the world. It’s a good reminder: Sometimes the simple answer is the right one.

Let’s revisit safety one last time with our new knowledge. Why does 5V not hurt you?

Why does wet skin change things?

Why is 110V Wall Power deadly?

Conclusion: Keep your voltage low, or keep your resistance high (wear shoes, stay dry).

In electronics, numbers get very big and very small quickly. Writing “0.000001 Amps” is annoying. Engineers use prefixes.

| Prefix | Symbol | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kilo | k | Thousand (x1,000) | 10kΩ Resistor (10,000 Ohms) |

| Mega | M | Million (x1,000,000) | 10MΩ Resistance (Dry Skin) |

| Milli | m | Thousandth (/1,000) | 20mA Current (LED) |

| Micro | µ | Millionth (/1,000,000) | 10µF Capacitor |

You will see “GND” everywhere on schematics. In our Water Analogy, Ground is Sea Level. It is just a reference point. When we say a tank is “10 feet high,” we mean “10 feet above Sea Level.” When we say a battery is “5 Volts,” we mean “The positive side is 5 Volts higher than the Ground side.”

Once you understand these three concepts, you will never look at the world the same way again. You won’t just see a light switch; you will see a valve controlling the flow of invisible particles. You won’t just see a battery; you will see a pressurized tank waiting to be unleashed. You are beginning to see the Matrix.

We finally pick up the hardware. Tomorrow, we are going to dissect the Breadboard. It is that mysterious white plastic block with all the holes. Beginners hate it because they don’t know how it’s wired inside. We will stick X-Ray vision on it, explain every hole, and build our very first circuit: The LED Flashlight.

Stay tuned.

Q: Can I use Ohm’s Law for AC (Wall power)? A: Mostly yes, but AC adds complexity (Frequency). For DC (Batteries/Arduino), Ohm’s Law is absolute law.

Q: What happens if resistance is zero? A: I = V / 0. Current becomes infinite. This is a short circuit. Boom.

Q: Why is Current “I”? A: It stands for Intensité du Courant (Intensity of Current). French scientists were pioneers in early electricity!

Q: Is water a good conductor? A: Pure water is actually an insulator! But tap water has minerals (salts) dissolved in it, which makes it conductive. This is why you shouldn’t use a toaster in the bath.

Q: What is a “Multi”-meter? A: It’s called “Multi” because it combines a Voltmeter, Ammeter, and Ohmmeter into one device. Before the 1970s, you had to buy three separate boxes.

Q: Why do resistors come in weird numbers like 220 and 4.7k? A: They follow a logarithmic scale called the E-series (E12/E24). It’s designed so that the gaps between values are consistent percentages. A 220 Ohm resistor is a standard value because it sits nicely between 100 and 1000. We will learn more about this when we decode the colored stripes.

Q: Does length of wire matter? A: Yes! Longer wire = More Resistance (More friction). Thinner wire = More Resistance. Just like pipes. A 10-mile long straw is harder to blow through than a 1-inch straw.